How is Japan's youth fighting against overwork?

Japan’s work culture has faced intense scrutiny since the 2015 death of Matsuri Takahashi, a 24-year-old employee who took her own life due to extreme overwork. Officially recognised as karoshi—death by overwork—her case sparked nationwide debate and pushed lawmakers to introduce reforms. Yet, as younger workers increasingly reject long hours and rigid gender roles, the country’s new prime minister has taken a starkly different stance.

Takahashi’s death exposed the harsh realities of Japan’s corporate world. Working over 100 hours of unpaid overtime in a single month, she left behind records of distressing messages about her workload. The tragedy prompted legal action against her employer, Dentsu, and led to stricter labour regulations under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. New laws now cap weekly overtime and encourage companies to adopt flexible working practices.

The younger generation has since pushed back against the culture that contributed to Takahashi’s death. Millennials and Gen Z workers are refusing unpaid overtime, with surveys showing a drop from 30% acceptance in 2020 to under 20% today. Movements like *quiet quitting*—doing the bare minimum at work—and government-backed *Premium Friday* campaigns, which urge employees to leave early, reflect this shift. Many now prioritise work-life balance over the gruelling *salaryman* lifestyle. Traditional workplace norms have also come under fire. Women in Japan have long been confined to supportive roles, such as secretarial or part-time work, while men dominate high-pressure, long-hour positions. This divide has kept female full-time employment around 50%, creating an *M-shaped* employment curve where women often leave work mid-career. Younger workers, however, are challenging these expectations, demanding more equitable opportunities. Despite these changes, Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, has openly rejected the push for balance. Her philosophy—'*work, work, work, work, and keep working*'—contrasts sharply with the reforms and shifting attitudes of recent years. Her stance has reignited debates over whether Japan’s corporate culture can truly evolve or if deep-rooted expectations will persist.

Takahashi’s death triggered legal and cultural shifts, but Japan’s work culture remains in transition. While younger employees resist overwork and outdated gender roles, political leaders like Takaichi signal a potential return to older values. The tension between reform and tradition will likely shape the country’s labour landscape for years to come.

Read also:

- American teenagers taking up farming roles previously filled by immigrants, a concept revisited from 1965's labor market shift.

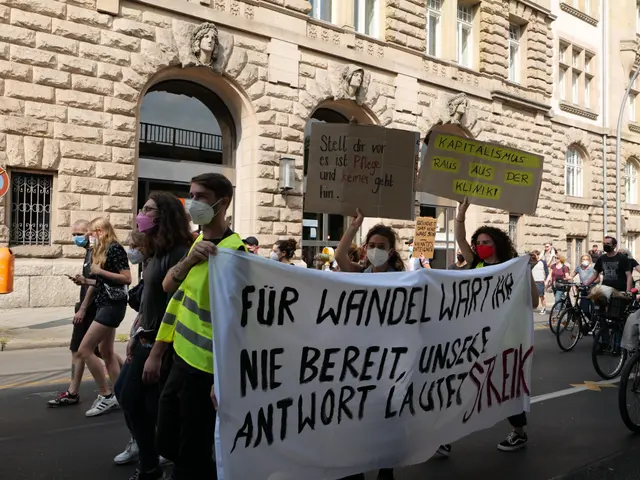

- Weekly affairs in the German Federal Parliament (Bundestag)

- Landslide claims seven lives, injures six individuals while they work to restore a water channel in the northern region of Pakistan

- Escalating conflict in Sudan has prompted the United Nations to announce a critical gender crisis, highlighting the disproportionate impact of the ongoing violence on women and girls.